As demonstrated by the above video of an interview done by CNN while the Forrest license plate is the topic of the segment the argument quickly shifts to southern identity. The head of the Mississippi NAACP, Derrick Johnson, states that the NAACP opposes the commemoration of any confederate soldiers because they were traitors to the union. Mr. Johnson even goes so far as to call Jefferson Davis the worst traitor in American history, a title normally reserved for Benedict Arnold. On the other hand the representative of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, Garret Stewart, states that the reason for the license plate tag is to repair civil war flags that northern states have returned to the south since the end of the war. Mr. Garret also points out that the Nathan Bedford Forrest license plate tag is not the only one they have proposed. He makes special mention that a tag of Jefferson Davis' home was released this year for sale to he public. Mr. Johnson's response was simply that the NAACP opposes all of these license plate tags simply on the fact that they commemorate the confederacy. This comment is crucial to the argument at hand as it is a clear cut example of the NAACP being opposed to the historic south. Many southerns hold the civil war to be part of their heritage and part of their cultural identity. As such this shows that the debate about Forrest's memory is actually just a focal point for the debate about the historic and cultural identity of Mississippi and the entirety of the South.

Sunday, April 24, 2011

Forrest as a Focal Point

As stated in previous posts the debate about the Nathan Bedford Forrest license plate tag revolves around the issue of what individuals believe he did during his life. Through extensive research it has be demonstrated that the legacy of Nathan Bedford Forrest can not be summed up as good or bad or even as racist or non-racist. Forrest was a Man of complex character one who was a slave trader but also offered to treat black union soldiers as prisoners of war not property. And while it has been historically proven he was a member of the KKK and its first Grand Wizard there is evidence to suggest that the first KKK was largely acting as a resistance group against policies of northern politicians. Policies that many southerns at the time believed were unfair to former confederate soldiers. However all of these qualities are not unique to Forrest rather they are representative of the struggle that exists in all southerners. The NAACP has stated numerous times in the debates over the Forrest license plate that there is a larger argument than simply that of the memory of Nathan Beford Forrest. Forrest has become the focal point for the debate about the history of the south as well as how southerners should identify themselves today.

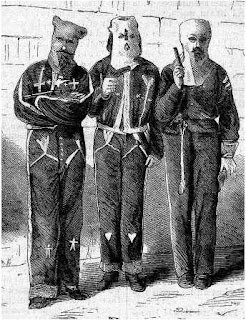

Forrest the Klansman

One of the primary claims of the NAACP is that Nathan Bedford Forrest should not be honored because of his role as the first grand wizard of the KKK. the Sons of Confederate Veterans disputes this claim and that Forrest was even part of the Klan. While it is difficult to determine specifics about the early days of the Klan due to its secrecy there is documented evidence of Forrest's involvement in the Klan. "A son of ex-confederate major Minor Meriwether wrote of an evening in 1867 when "several of father's friends" came to the Meriwether home in Memphis "to discuss the Ku Klux Klan and how it might save Memphis and the South from Bankruptcy (Hurst P.290)." Meriwethers son would later write the names of several of his father's friends which "included Forrest Isham G. Harris, "General Gordon of Georgia," and Avalanche editor Matthew Gallaway (Hurst P.290)." While accounts such as this place Forrest at meetings they do not show him as a founding member of the Klan. The reality of the situation is that Forrest was not a founding member of the KKK, the most excepted stories of the birth of the Klan name the Pulaski club as the original name of the organization. In fact one of the actual co-founders James R. Crowe is quoted as stating that the Klan sought Forrest out. "So we chose General N.B. Forrest...He was made a member and took the oath in room No. 10 at Maxwell House...in the fall of 1866. The oath was administered to him by Captain J.W. Morton...(Hurst P.285)." This is important because to this point in time the Ku Klux Klan was little more than a social group. Started in Pulaski, Tennessee in late 1865 early 1866 the original KKK did little more than dress in sheets and scare freedmen after dark by pretending to be the spirits of dead confederate soldiers. By the time of Forrest's induction in the fall of 1866 the KKK had expanded outside of its birth place of Pulaski into numerous groups with little or no affiliation. It was at this point that it was determined that the Klan should be organized into a single national entity. The members of the Ku Klux Klan met one night in their traditional meeting place of Maxwell House Hotel to decide who should lead them. "Nominations were solicited. "The Wizard of the Saddle, General Nathan Bedford Forrest," a voice from the back of the room called out. The nominee was elected quickly, and in keeping with the off-the-cuff impulsiveness of the Early Klan, was designated grand wizard of the Invisible Empire (Hurst P.287)."While the early days of the Klan are shrouded in mystery this account is widely believed to be the most accurate.

While it widely excepted that Forrest Broke Ties with the KKK before the end of the 1860's the reason for their break remains unclear. Supporters of Forrest's legacy claim it because the KKK was becoming unorganized and violent. Forrest Himself claimed that the Ku Klux Klan was nothing more than a political organization. "Although Forrest and others later insisted that the Klan functioned only as a political organization, racial terrorism became the hallmark of Klan activities. Forrest, however lost interest in the Klan once it outgrew his immediate authority (Carney P. 603)." Author Jack Hurst gives some credibility to Forrest's claim as he describes numerous instances in which Forrest becomes part of southern democratic politics after joining the KKK. "On June 1 Forrest and a number of Known or suspected Klansmen and/or personally close to its Grand wizard were included among a total of forty-nine delegates named to go to the Nashville state convention a week later (Hurst P.297)." Subsequently there are numerous documented instances of Klansmen taking part in democratic assemblies as well as petitioning of governors. However these could simply be because many Klansmen were men of prominence seeking to regain their right to vote. But while one function of the Klan may have been political gain another function was that of oppression and terror.

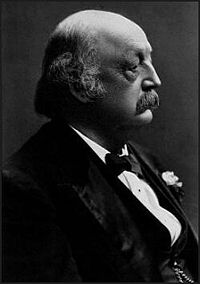

The Civil Rights act of 1871. also known as the Ku Klu Klan act, was the project bill of Benjamin Franklin Butler (pictured above). The KKK act was a direct response to the growing violence against African-Americans in the south by the KKK. While the KKK had become a national organization at this time it is unclear how much control its grand wizard had over chapters outside of Tennessee. However what is clear, and heavily documented, is that the KKK began acting freed blacks and denying them their right to vote. Under the Klan act federal troops rather than local militia were used to enforce the law. And instead of being tried in local courts those known or accused of being Klansmen were tired in federal courts with much higher conviction rates than ever before. The Klan act decimated the Ku Klux Klan fining and imprisoning vast numbers of its members making the Klan non-existent until its resurrection in 1915. However while Butler's bill was the death knell of the early Klan Forrest is reported to have disavowed the Klan years before the implementation of the Klan act. While this is a near certainty what remains unclear is what role Forrest played in the actions that lead to the proposal of the Klan act in the First place. This like many things in Forrest's life is subject to interpretation and uncertainty.

While it widely excepted that Forrest Broke Ties with the KKK before the end of the 1860's the reason for their break remains unclear. Supporters of Forrest's legacy claim it because the KKK was becoming unorganized and violent. Forrest Himself claimed that the Ku Klux Klan was nothing more than a political organization. "Although Forrest and others later insisted that the Klan functioned only as a political organization, racial terrorism became the hallmark of Klan activities. Forrest, however lost interest in the Klan once it outgrew his immediate authority (Carney P. 603)." Author Jack Hurst gives some credibility to Forrest's claim as he describes numerous instances in which Forrest becomes part of southern democratic politics after joining the KKK. "On June 1 Forrest and a number of Known or suspected Klansmen and/or personally close to its Grand wizard were included among a total of forty-nine delegates named to go to the Nashville state convention a week later (Hurst P.297)." Subsequently there are numerous documented instances of Klansmen taking part in democratic assemblies as well as petitioning of governors. However these could simply be because many Klansmen were men of prominence seeking to regain their right to vote. But while one function of the Klan may have been political gain another function was that of oppression and terror.

The Civil Rights act of 1871. also known as the Ku Klu Klan act, was the project bill of Benjamin Franklin Butler (pictured above). The KKK act was a direct response to the growing violence against African-Americans in the south by the KKK. While the KKK had become a national organization at this time it is unclear how much control its grand wizard had over chapters outside of Tennessee. However what is clear, and heavily documented, is that the KKK began acting freed blacks and denying them their right to vote. Under the Klan act federal troops rather than local militia were used to enforce the law. And instead of being tried in local courts those known or accused of being Klansmen were tired in federal courts with much higher conviction rates than ever before. The Klan act decimated the Ku Klux Klan fining and imprisoning vast numbers of its members making the Klan non-existent until its resurrection in 1915. However while Butler's bill was the death knell of the early Klan Forrest is reported to have disavowed the Klan years before the implementation of the Klan act. While this is a near certainty what remains unclear is what role Forrest played in the actions that lead to the proposal of the Klan act in the First place. This like many things in Forrest's life is subject to interpretation and uncertainty.

Saturday, April 23, 2011

Fort Pillow "Massacre"

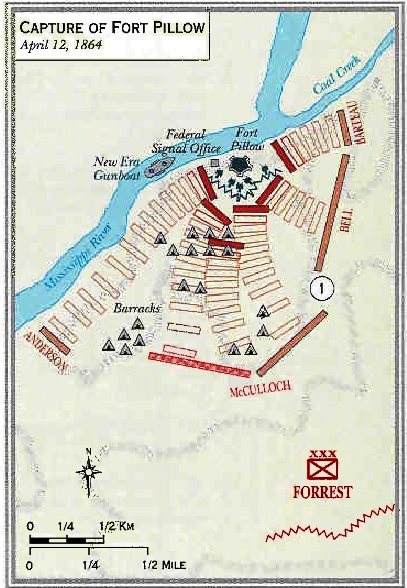

Contrary to reports from northern newspapers about Forrest's intentions at Paducah Forrest did not attack Fort Pillow because it was garrisoned by Black troops. Rather the reason for his attack was its supply stores as he stated when writing to General Leonidas Polk after Paducah, "There is a Federal force of 500 or 600 at Fort Pillow, which I shall attend to in a day or two, as they have horses and supplies which we need (Hurst P.164)." The reason for Forrest's needing of supplies was largely due to the fact that he had been given a new detachment of soldiers. "About the 1st of March, 1864, Brigadier General Abe Buford...was ordered to report to Forrest in Mississippi, and to take with him the fragments of three Kentucky infantry regiments which had formerly served in Bragg's army (Wyeth P.299)." These fragmented Kentucky regiments had applied to become mounted infantry largely because they had been "decimated in the numerous battles and hardships through which they had passed (Wyeth P.299)." However at this point in the war the confederate government was not able to provide the horses and supplies needed for these men. Supplying his men and obtaining the necessary horses for his new troops was the reason for Forrest's campaign in western Tennessee in March and April 1864. His quest for these supplies would lead him to numerous engagements including Paducah. During this time, as stated in a previous post, Forrest and his men were repeatedly insulted by Union forces and northern newspapers. All of these events would ultimately culminate in the action at Fort Pillow in early April 1864.

Fort Pillow had a Union Garrison made up of the 13th Tennessee Cavalry and two black artillery units the 6th heavy artillery and 2nd U.S. light Artillery. Records estimate the Garrison was approximately 580 men, six artillery pieces, and the Union gun boat New Era in the Mississippi river. What later news paper reports fail to reference is that fact that nearly half the force of 580 men at Fort Pillow were black troops. This high concentration of black troops helps explain the numbers reported by northern papers following Forrest's assault. The commanding Union officer, Major L.F. Booth, was assigned to the Fort on March 28th barely two weeks before Forrest's attack. Booth was so confident in his position, partially because of the reports from northern news papers in the previous weeks, that on April 3rd he wrote to his commanding officer General S.A. Hurlbut that "Everything is quiet within a radius of thirty or forty miles around, and I do not think any apprehensions need be felt of fears entertained in reference to this place being attacked or even threatened; I think it perfectly safe (Wyeth P.313)." Ironically Booth wrote this letter the day before Forrest wrote his commanding officer expressing his intent to take Fort Pillow and all its supplies.

May 10, 1864 was the day that Forrest's forces began to move against Fort Pillow. The actual attack began on April 12th and met with initial success. "All the confederates advanced to the charge the moment the rifles were cracking at the picket line, and so sudden was the attack that the Federals abandoned the entire outer line of defenses without serious resistance (Wyeth P.315)." Upon taking the initial defensive lines the confederate forces were able to establish positions for sharpshooters as well as sealing off Fort Pillow to prevent escape via land. The confederate sharp shooters would prove incredibly affective during the assault on Fort Pillow as Union Adjutant Mack J. Leaming reported. "We suffered pretty severly in the loss of commissioned officers by the unerring aim of the rebel sharp shooters, and among this loss I have to record out post commander, Major L. F. Booth, who was killed almost instantly by a Musket-ball through the breast (Wyeth P.315)." The death of Major Booth would prove to be a crucial loss for the defenders of Fort Pillow as his replacement Major W.F. Bradford was very inexperienced. By noon on April 12th Nathan Bedford Forrest had arrived at Fort Pillow to take direct command of his already attacking army.It is at this point that the controversy over Forrest's actions at Fort Pillow begin to take shape. The NAACP and other anti-Forrest persons call Fort Pillow a Massacre. The principle claim is that Forrest ordered the slaughter of hundreds of Black troops as they were trying to surrender. However as evidence indicates the situation is far more complicated than a commanding officer issuing an order of slaughter.

Upon arrival at Fort Pillow one of the first things Forrest did was send a messenger in under a white flag of truce to demand the honorable surrender of the Garrison. Forrest's message was his normal message even though prior to arriving he knew that nearly half the garrison were black soldiers. "Major, - The conduct of the officers and men garrisoning Fort Pillow has been such as to entitle them to being treated as prisoners of war. I demand the unconditional surrender of this garrison, promising you that you shall be treated as prisoners of war. My men, have received a fresh supply of ammunition, and from their present position can easily assault and capture the fort. Should my demand be refused, I cannot be responsible for the fate of your command (Hurst P.169)." It is at this point that the issue of black union soldiers comes to the forefront of the debate, how would they be treated if they surrendered? A confederate soldier Captain Walter A. Goodman was present at the time that Forrest and his officers discussed the treatment of the black union soldiers should they surrender. "There was a discussion about it among the officers present, and it was asked whether it was intended to include the negro soldiers as well as the white; to which both General Forrest and General Chalmers replied that it was so intended, and that if the fort surrendered, the whole garrison, white and black, should be treated as prisoners of war (Morris P.31)." What Goodman wrote is incredibly important as it made a historic record of the fact that both General Forrest and General Chalmers agreed that the black soldiers would be treated as equal soldiers. A statement such as this would not be characteristic of a man bent on "killing as many Negros as possible," as many northern newspapers had stated at this time. However this would become a moot point as the Union commander, Major Bradford, who was pretending to be Major Booth did not surrender .

Fort Pillow had a Union Garrison made up of the 13th Tennessee Cavalry and two black artillery units the 6th heavy artillery and 2nd U.S. light Artillery. Records estimate the Garrison was approximately 580 men, six artillery pieces, and the Union gun boat New Era in the Mississippi river. What later news paper reports fail to reference is that fact that nearly half the force of 580 men at Fort Pillow were black troops. This high concentration of black troops helps explain the numbers reported by northern papers following Forrest's assault. The commanding Union officer, Major L.F. Booth, was assigned to the Fort on March 28th barely two weeks before Forrest's attack. Booth was so confident in his position, partially because of the reports from northern news papers in the previous weeks, that on April 3rd he wrote to his commanding officer General S.A. Hurlbut that "Everything is quiet within a radius of thirty or forty miles around, and I do not think any apprehensions need be felt of fears entertained in reference to this place being attacked or even threatened; I think it perfectly safe (Wyeth P.313)." Ironically Booth wrote this letter the day before Forrest wrote his commanding officer expressing his intent to take Fort Pillow and all its supplies.

May 10, 1864 was the day that Forrest's forces began to move against Fort Pillow. The actual attack began on April 12th and met with initial success. "All the confederates advanced to the charge the moment the rifles were cracking at the picket line, and so sudden was the attack that the Federals abandoned the entire outer line of defenses without serious resistance (Wyeth P.315)." Upon taking the initial defensive lines the confederate forces were able to establish positions for sharpshooters as well as sealing off Fort Pillow to prevent escape via land. The confederate sharp shooters would prove incredibly affective during the assault on Fort Pillow as Union Adjutant Mack J. Leaming reported. "We suffered pretty severly in the loss of commissioned officers by the unerring aim of the rebel sharp shooters, and among this loss I have to record out post commander, Major L. F. Booth, who was killed almost instantly by a Musket-ball through the breast (Wyeth P.315)." The death of Major Booth would prove to be a crucial loss for the defenders of Fort Pillow as his replacement Major W.F. Bradford was very inexperienced. By noon on April 12th Nathan Bedford Forrest had arrived at Fort Pillow to take direct command of his already attacking army.It is at this point that the controversy over Forrest's actions at Fort Pillow begin to take shape. The NAACP and other anti-Forrest persons call Fort Pillow a Massacre. The principle claim is that Forrest ordered the slaughter of hundreds of Black troops as they were trying to surrender. However as evidence indicates the situation is far more complicated than a commanding officer issuing an order of slaughter.

Upon arrival at Fort Pillow one of the first things Forrest did was send a messenger in under a white flag of truce to demand the honorable surrender of the Garrison. Forrest's message was his normal message even though prior to arriving he knew that nearly half the garrison were black soldiers. "Major, - The conduct of the officers and men garrisoning Fort Pillow has been such as to entitle them to being treated as prisoners of war. I demand the unconditional surrender of this garrison, promising you that you shall be treated as prisoners of war. My men, have received a fresh supply of ammunition, and from their present position can easily assault and capture the fort. Should my demand be refused, I cannot be responsible for the fate of your command (Hurst P.169)." It is at this point that the issue of black union soldiers comes to the forefront of the debate, how would they be treated if they surrendered? A confederate soldier Captain Walter A. Goodman was present at the time that Forrest and his officers discussed the treatment of the black union soldiers should they surrender. "There was a discussion about it among the officers present, and it was asked whether it was intended to include the negro soldiers as well as the white; to which both General Forrest and General Chalmers replied that it was so intended, and that if the fort surrendered, the whole garrison, white and black, should be treated as prisoners of war (Morris P.31)." What Goodman wrote is incredibly important as it made a historic record of the fact that both General Forrest and General Chalmers agreed that the black soldiers would be treated as equal soldiers. A statement such as this would not be characteristic of a man bent on "killing as many Negros as possible," as many northern newspapers had stated at this time. However this would become a moot point as the Union commander, Major Bradford, who was pretending to be Major Booth did not surrender .

Upon receiving Forrest's surrender demand Major Bradford, acting under Booth's name, requested an hour to make his decision; Forrest granted his request. However Forrest would find his generosity misplaced as Bradford attempted to use this hour to land reinforcements via the gunboats Olive Branch and Liberty. After securing the bluffs and making it impossible to land reinforcements Forrest sent another message giving the defenders only twenty minutes to decide. Bradford's reply was brief, "General: I will not surrender. Very respectfully, your obedient servant, L.E Booth, commanding U.S. Forces, Fort Pillow (Morris P.31)." Shortly after Forrest received Bradford/Booth's reply the final assault began. It is at this point that the events of the previous weeks became significant. Coupled with events of simply getting to Fort Pillow Forrest's men were now in a fever pitch and in less than a forgiving mood. "The wrathful Confederates--most of whom had marched all night to the outskirts of the fort, run and sniped under enemy fire all morning, and then waited anxiously in the hot afternoon sun for the final assault to begin--were in no mood to be forgiving. To a man they believed that the Federals had been fools to refuse Forrest's surrender demand. That refusal had cost them another 100 good men, dead or wounded (Morris P.32)." The Confederates easily overtook the fort and the Union defenders fled from their posts and ran for the gun boats on the river below. But in the ensuing kayos men who were attempting to surrender were shot as some union soldiers kept firing back at the advancing confederates.DeWitt Clinton Fort, one of Forrest's men during the battle wrote in his diary shortly after the battle. "The wildest confusion prevailed among those who had run down the bluff. Many of them had thrown down their arms while running and seemed desirous to surrender while many others had carried their guns with them and were loading and firing back up the bluff as us with a desperation which seemed worse than senseless. We could only stand there and fire until the last man of them was ready to surrender (Morris P.32)." It is historically documented that Fort was a soldier for the confederacy during the civil war and attached to Forrest's command at this time therefore his account is highly credible. Subsequently Forrest gave an interview on the events of Fort Pillow some years after the war which was published in The Philadelphia Weekly Times. "The Negroes ran out down to the river; and although the white flag was flying, they kept on turning back and shooting ar my men, who consequently continued to fire into them crowded on the brink of the river, and they killed a good many of them in spite of my efforts and those of their officers to stop them. But there was no deliberate intention nor effort to massacre the garrison as has been so generally reported by the Northern papers (Morris P.32)." While this account is subject some speculation about Forrest trying to save his own reputation taken in conjunction with DeWitt Fort's account it is likely that the actual events resembled what these two men described. However those opposed to Forrest's memory hold that the slaughter was deliberate and intentional and this is likely do to the ruling of the Northern congressional committee chaired by Radical Republican Senator Benjamin E Wade. The committee found that Forrest was guilty of "an indiscriminate slaughter, sparing neither age nor sex, white or black, soldier or citizen (Morris P.33)," however this ruling in of itself is problematic as there were no women and children in the fort at the time of Forrest's assault. And the only civilian killed had taken up arms in defense of the fort and was by military law no longer a civilian. Ultimately this ruling carried no weight and when Forrest was brought up on charges after the war he was found to be innocent. However one thing is undeniable Forrest and his men did kill a large number of black troops at Fort Pillow, Forrest himself admitted this fact, but the fog of war prevents the real truth of history to be know. While it is probable that some men, both black and white, were killed while trying to surrender it is even more likely that many more were killed while firing their weapons in an attempt to escape the confederate forces. While the evidence fro either argument many never be completely conclusive Fort Pillow has left a mark on the Military record of Nathan Bedford Forrest that he is not likely to recover from any time soon.

Friday, April 22, 2011

Action leading up to Fort Pillow

According to the Sons of Confederate Veterans spokesman Greg Stewart the reason for the SCV selecting Nathan Bedford Forrest for their 2014 commemorative tag was his service to the confederacy during the Civil war. The SCV cites numerous engagements such as Chattanooga, Chickamauga, and Brice's Crossroads as examples of Forrest's military brilliance and bravery. However even with such exemplary marks on his service record Nathan Bedford Forrest's military service has a black mark on it called Fort Pillow.

While the "Fort Pillow Massacre" is seen by Forrest detractors as a demonstration of his racial views there are numerous documented events surrounding Fort Pillow that are ignored. According to author and editor of Military Heritage Magazine Roy Morris Jr. the actions of Union commanders and Norther news papers had a profound affect on the mind set of Forrest's troops. To understand the mindset of Forrest and his men prior to Fort Pillow it is first important to understand their demographics, as stated by Morris. "For Major General Nathan Bedford Forrest and the 3,000 troopers he led front northern Mississippi that March - Mostly Tennesseans who were eager to reenter their home state...(Morris P.26)" Forrest, who considered Tennessee his home was returning with men who had been forced out by the union occupation. As such any mistreatment of the locals would be taken far more seriously as it was quite possible they were family members of Forrest's men. Forrest himself commented on the state of the territory he was now entering, "The whole of West Tennessee is overrun by bands and squads of robbers, horse thieves and deserters, whose depredations and unlawful appropriations of private property are rapidly and effectually depleting the country(Morris P.26)." This undoubtedly had a profound affect on Forrest's men as it was their lively hoods that were being stolen.

As if the prospect of loss of property weren't enough reason for Forrest's men to fight the capture, torture, and subsequent murder of several of Forrest's subordinate commanders gave them even more reason to hate the union army in Tennessee. Forrest recounted the fate of Lieutenant Willis Dodds as described to him by a local witness to the crime. "Dodds had been put to death most horribly mutilated, the face having been skinned, the nose cut off the under jaw disjoined, the privates cut off, and the body otherwise barbarously lacerated and most injured (Morris P.26)." According to records this act was carried out by the forces of Colonel Fielding Hurst of the 6th Tennessee Cavalry (U.S.). The Tennessee 6th was also reportedly responsible for a large portion of the abuses against the citizens of western Tennessee. "These homemade Yankees were hated by Forrest's men, many of whose families reportedly had been victims of the turncoats' threats, abuses, and outright thievery (Morris P.26)." However the Tennessee 6th was not present at Fort Pillow rather Forrest and his men caught up to them in Bolivar, Tennessee; a battle in which Hurst would be resoundingly humiliated. However while the defeat of the Tennessee 6th provided Forrest and his men with some form of revenge they would all have their reputations insulted by numerous northern papers.

Paducah, Kentucky was a small town just over the Mississippi river between Western Tennessee and Eastern Kentucky. The battle that ensued was largely a diversionary maneuver as Forrest was more interested in taking the supplies in the town of Paducah rather than the Union fort outside of town. Forrest and his men easily took the city of Paducah, as recounted by 13th Tennesse cavalry commander Chalmers who moved into Paducah on orders from Forrest. "[We] drove Hurst hatless into Memphis, leaving in our hands all his wagons, ambulances, papers, and his mistresses, both black and white (Hurst P.163)." However while Paducah was a victory for Forrest's forces the Chicago Tribune as well as the Louisville Journal were reporting otherwise. The Louisville Journal reported that Forrest's men were ""gloriously drunk, and but little better than a mob which with wild cheers and blasphemous oaths...thronged the streets and commenced an indiscriminate pillage of the houses" (Hurst p.163)." Articles such as this made no mention of the Union force that Forrest and his men defeated, rather the northern papers painted a picture of drunk rebels invading a helpless town. As if this account wasn't enough of an insult The Emancipationist Tribune, an abolitionist paper, reported that "The rebels were repulsed [from the fort] at each assult, and about 9 o'clock P.m. skedaddled, after killing as many negroes as they could, which seems to have been their primary objective in coming to Paducah (Hurst 163-164)." While this article shows that the confederate force did not simply attack a helpless town it is only a partial description of the events that transpired. The attack The Emancipationist is speaking of is that of one of Forrest's subordinates, Colonel A.P. Thompson, without Forrest's knowledge. Additionally prior to the actions at Paducah Forrest's force had no prior knowledge of black troops in the area. Irregardless of what troops were stationed at Paducah Forrest mission in the town was to acquire as many supplies as possible. "Forrest had no intention of making a needless sacrifice of his troops in an assault. His objective was to hold the Federals there and on board of their gunboats until he could remove all the supplies and horses which could be obtained from Paducah (Wyeth P.299)." The inaccurate news reports from the northern press undoubtedly had an affect of the attitude of Forrest and his men as they began marching for Fort Pillow. The accusations of being little more than a drunken mob taking advantage of a defenseless city as wells as being repulsed with ease by former slaves undoubtedly angered Forrest and his men. The anger felt by Forrest's men would not be assuaged in the coming days. In fact when the final assault on Fort Pillow began their tempers would be at the boiling point.

While the "Fort Pillow Massacre" is seen by Forrest detractors as a demonstration of his racial views there are numerous documented events surrounding Fort Pillow that are ignored. According to author and editor of Military Heritage Magazine Roy Morris Jr. the actions of Union commanders and Norther news papers had a profound affect on the mind set of Forrest's troops. To understand the mindset of Forrest and his men prior to Fort Pillow it is first important to understand their demographics, as stated by Morris. "For Major General Nathan Bedford Forrest and the 3,000 troopers he led front northern Mississippi that March - Mostly Tennesseans who were eager to reenter their home state...(Morris P.26)" Forrest, who considered Tennessee his home was returning with men who had been forced out by the union occupation. As such any mistreatment of the locals would be taken far more seriously as it was quite possible they were family members of Forrest's men. Forrest himself commented on the state of the territory he was now entering, "The whole of West Tennessee is overrun by bands and squads of robbers, horse thieves and deserters, whose depredations and unlawful appropriations of private property are rapidly and effectually depleting the country(Morris P.26)." This undoubtedly had a profound affect on Forrest's men as it was their lively hoods that were being stolen.

As if the prospect of loss of property weren't enough reason for Forrest's men to fight the capture, torture, and subsequent murder of several of Forrest's subordinate commanders gave them even more reason to hate the union army in Tennessee. Forrest recounted the fate of Lieutenant Willis Dodds as described to him by a local witness to the crime. "Dodds had been put to death most horribly mutilated, the face having been skinned, the nose cut off the under jaw disjoined, the privates cut off, and the body otherwise barbarously lacerated and most injured (Morris P.26)." According to records this act was carried out by the forces of Colonel Fielding Hurst of the 6th Tennessee Cavalry (U.S.). The Tennessee 6th was also reportedly responsible for a large portion of the abuses against the citizens of western Tennessee. "These homemade Yankees were hated by Forrest's men, many of whose families reportedly had been victims of the turncoats' threats, abuses, and outright thievery (Morris P.26)." However the Tennessee 6th was not present at Fort Pillow rather Forrest and his men caught up to them in Bolivar, Tennessee; a battle in which Hurst would be resoundingly humiliated. However while the defeat of the Tennessee 6th provided Forrest and his men with some form of revenge they would all have their reputations insulted by numerous northern papers.

Paducah, Kentucky was a small town just over the Mississippi river between Western Tennessee and Eastern Kentucky. The battle that ensued was largely a diversionary maneuver as Forrest was more interested in taking the supplies in the town of Paducah rather than the Union fort outside of town. Forrest and his men easily took the city of Paducah, as recounted by 13th Tennesse cavalry commander Chalmers who moved into Paducah on orders from Forrest. "[We] drove Hurst hatless into Memphis, leaving in our hands all his wagons, ambulances, papers, and his mistresses, both black and white (Hurst P.163)." However while Paducah was a victory for Forrest's forces the Chicago Tribune as well as the Louisville Journal were reporting otherwise. The Louisville Journal reported that Forrest's men were ""gloriously drunk, and but little better than a mob which with wild cheers and blasphemous oaths...thronged the streets and commenced an indiscriminate pillage of the houses" (Hurst p.163)." Articles such as this made no mention of the Union force that Forrest and his men defeated, rather the northern papers painted a picture of drunk rebels invading a helpless town. As if this account wasn't enough of an insult The Emancipationist Tribune, an abolitionist paper, reported that "The rebels were repulsed [from the fort] at each assult, and about 9 o'clock P.m. skedaddled, after killing as many negroes as they could, which seems to have been their primary objective in coming to Paducah (Hurst 163-164)." While this article shows that the confederate force did not simply attack a helpless town it is only a partial description of the events that transpired. The attack The Emancipationist is speaking of is that of one of Forrest's subordinates, Colonel A.P. Thompson, without Forrest's knowledge. Additionally prior to the actions at Paducah Forrest's force had no prior knowledge of black troops in the area. Irregardless of what troops were stationed at Paducah Forrest mission in the town was to acquire as many supplies as possible. "Forrest had no intention of making a needless sacrifice of his troops in an assault. His objective was to hold the Federals there and on board of their gunboats until he could remove all the supplies and horses which could be obtained from Paducah (Wyeth P.299)." The inaccurate news reports from the northern press undoubtedly had an affect of the attitude of Forrest and his men as they began marching for Fort Pillow. The accusations of being little more than a drunken mob taking advantage of a defenseless city as wells as being repulsed with ease by former slaves undoubtedly angered Forrest and his men. The anger felt by Forrest's men would not be assuaged in the coming days. In fact when the final assault on Fort Pillow began their tempers would be at the boiling point.

Thursday, April 21, 2011

Pre Civil war Forrest

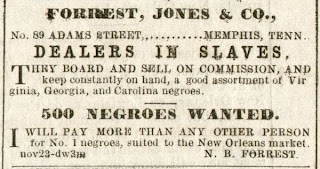

The controversy over the commemoration of Nathan Bedford Forrest centers on his history with Afircan Americans. It is a well documented fact that prior to the Civil War Forrest was a successful slave trader in Tennessee. Les Smith, a reporter for fox news, cites an advertisement from 1857 posted in the Appeal which describes Forrest's "slave mart" as one of the more humane and well stocked in Memphis. Advertisements such as the image below were common place in Tennessee news papers as Forrest and his business partners sought new "products" to market to white Tennesseans.

While the evidence is undeniable that Forrest was a successful slave trader, "by the late 1850's Forrest claimed to be worth over a million dollars (Carney P.602)," supporters of his commemoration believe he was a kind slave trader. Writer Lafacadio Hearn wrote of how Forrest treated his slaves while attending his funeral in 1877, "King to his Negros; that he never separated members of a family, and that he always told his slaves to go out into the city and choose their own masters." However this was written nearly 20 years after Forrest had joined the confederate army and nearly immediately after his death as such it is subject scrutiny. However another man Colonel George W. Adair, who was associated with Forrest during his years as a slave trader, wrote of relationships with "his Negros." "[Forrest] was overwhelmed with applications from many of this class, who begged him to purchase them...[Forrest] was very careful when he purchased a married slave to use every effort to secure also the husband or wife, as the case might be, and unite them, and in handling children he would not permit the separation of a family." But while there exists historical documentation attesting to Forrest's humanity with his slaves the NAACP and many African Americans take a different opinion of Forrest's treatment of his slaves.

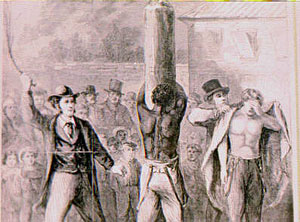

Detractors from the glorification of Forrest believe that Forrest was far more cruel to his slaves and as with his supporters there are historical documents to this effect. In 1864 the New York Tribune published a dispatch that described the conditions of the slave yards as "a perfect horror to all Negros far and near." The same dispatch goes on to describe the measures Forrest would take to punish his slaves. "Forrest and his crippled brother John would stand one on each side and cut up the victim with bullwhips until the blood trickled to the ground." While this information is from a historic news paper it still has the same short comings as the passage by Lafacadio Hearn. The New York Tribune wrote and published this article near the end of the civil war and not long after the "Fort Pillow Massacre" became public knowledge. As such this piece is also subject to scrutiny as it is likely that this piece was written as propaganda to create support for the union and for the liberation of enslaved blacks. While there are conflicting historical accounts about how Nathan Bedford Forrest treated his slaves one thing is certain and that is that he was a slave trader. And regardless of how he treated his slaves the fact that Forrest was a slave trader is one of the key issues surrounding his legacy.

While the evidence is undeniable that Forrest was a successful slave trader, "by the late 1850's Forrest claimed to be worth over a million dollars (Carney P.602)," supporters of his commemoration believe he was a kind slave trader. Writer Lafacadio Hearn wrote of how Forrest treated his slaves while attending his funeral in 1877, "King to his Negros; that he never separated members of a family, and that he always told his slaves to go out into the city and choose their own masters." However this was written nearly 20 years after Forrest had joined the confederate army and nearly immediately after his death as such it is subject scrutiny. However another man Colonel George W. Adair, who was associated with Forrest during his years as a slave trader, wrote of relationships with "his Negros." "[Forrest] was overwhelmed with applications from many of this class, who begged him to purchase them...[Forrest] was very careful when he purchased a married slave to use every effort to secure also the husband or wife, as the case might be, and unite them, and in handling children he would not permit the separation of a family." But while there exists historical documentation attesting to Forrest's humanity with his slaves the NAACP and many African Americans take a different opinion of Forrest's treatment of his slaves.

Detractors from the glorification of Forrest believe that Forrest was far more cruel to his slaves and as with his supporters there are historical documents to this effect. In 1864 the New York Tribune published a dispatch that described the conditions of the slave yards as "a perfect horror to all Negros far and near." The same dispatch goes on to describe the measures Forrest would take to punish his slaves. "Forrest and his crippled brother John would stand one on each side and cut up the victim with bullwhips until the blood trickled to the ground." While this information is from a historic news paper it still has the same short comings as the passage by Lafacadio Hearn. The New York Tribune wrote and published this article near the end of the civil war and not long after the "Fort Pillow Massacre" became public knowledge. As such this piece is also subject to scrutiny as it is likely that this piece was written as propaganda to create support for the union and for the liberation of enslaved blacks. While there are conflicting historical accounts about how Nathan Bedford Forrest treated his slaves one thing is certain and that is that he was a slave trader. And regardless of how he treated his slaves the fact that Forrest was a slave trader is one of the key issues surrounding his legacy.

Wednesday, April 20, 2011

The Debate begins

The Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV) is an organization for individuals who are descended from confederate soldiers. In conjunction with the United Daughters of the Confederacy they are responsible for the majority of the civil war monuments as well as civil war commemoration events. As part of the 150th anniversary the SCV has submitted designs for commemorative license plates to be issued one at a time until 2015. However the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) opposes these designs. In particular the NAACP has brought national attention to a design that would commemorate confederate Lieutenant-General Nathan Bedford Forrest. Forrest was and continues to be a man of immense controversy. During his life he was both a slave trader and the First Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan. Forrest has also been accused of slaughtering black Union soldiers at what has come to be known as the "Fort Pillow Massacre." The NAACP has petitioned the governor of Mississippi, Haley Barbour, to denounce the proposed license plate tag and prevent it from reaching the state congress for consideration. Governor Barbour has publicly declined to denounce the SCV proposal on the grounds that it simply doesn't have enough support to become law. As straight forward as this debate seems at the surface it is anything but. Getting to the truth about the life of Nathan Bedford Forrest is difficult as what is fact and what is fiction has become highly politicized since Forrest's death in 1877. Forrest was used as an example of antebellum southern values in the late 19th century, he became a symbol of greatness of the south's past. But his identity shifted during the early 20th century as people used his ties to the early KKK to turn him into the great white hope of the Jim Crow era south. However whites were not the only group to use Forrest as an example for their cause. During the civil right movement of the 1950's and 60's African Americans began to use Forrest as an example of white southern hatred. Forrest's image and memory have been invoked throughout the south over generations as the poster boy for their cause. As such the facts surrounding Nathan Bedford Forrest are not always easy to get to. One thing is certain though Nathan Bedford Forrest and his legacy have become the focal point for the debate over the history and culture of the American South.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)